By Sandhya Sridhar

The Madras Devadasi Act (Prevention of Dedication) was passed soon after Independence, in the Madras Presidency, in October 1947. A little earlier, the Bombay Presidency had also passed an act for the protection of devadasis and the prevention of their dedication, in 1934. (Similar acts in a few other states of India came into force much later.) The devadasi tradition at that point was seen as a degradation of women, and their dedication to the temple, almost an initiation into prostitution. However, history is kinder to the devadasi, who was seen as the ‘nithyasumangali’, or ‘one who is always auspicious’ and who can never be widowed, and thus wore the symbols of her marital status till death. The devadasi was well-versed in the arts, and her life was intrinsically tied to the temple she was dedicated to, its rituals and festivals.

The tradition of the devadasis, or women dedicated to the service of the Lord, harks back to ancient times. The devadasi could dance, sing, was well-versed in literature and poetry, and had temple duties to perform. She was often quite wealthy, the ruler having bestowed land on her for her sustenance.

Think of a dancing girl and what image comes to mind is the eponymous dancing girl icon of the Indus Valley. She stands confident, hand on a hip, her body language clearly assertive. However, she remains an enigma, her real story shrouded in the mists of time.

In the later periods, however, there are enough records of women in the ‘service of the temple’. While Kautilya speaks of one such in his writings in the fourth century B.C., the Ramgarh cave inscriptions speak of a ‘girl in the service of god’. This kind of written record of women who were dancers and singers, and who served in temples, continues into the medieval period. A woman named Thillaivanamudaiyal Madavalli, for example, was a servant of the Siva temple at Tirumananjeri, in about 1090. During this period in history in South India, devadasis were given their own symbols of prestige, like a flag, or a palanquin. Some devadasis had hereditary rights in temples as well.

Young girls were dedicated to temples by their families, and some even became devadasis voluntarily. For example, there are records of parents of a devadasi taking the permission of the village council before dedicating their daughter to the service of the Lord, in the Adhipurisvara temple. Many young girls were dedicated to Sriranganathar in Srirangam, by their families. The families that did this were from across the caste spectrum. In fact, the early Cholas, who built many temples, codified the roles of the devadasis in the temples. Rajarajan I was instrumental in this, and the devadasis had defined roles, some to dance at appointed ritual times, others to sing or make a chorus during the auspicious time, performing arati or lighting the lamps in the evenings.

Rajas of various eras made gifts of gold and land to the devadasis, offering them almost independent fiefdom, giving them a status that was very different from the other women in society in those times. Such records of grants and gifts exist across the various regions of South India during medieval times.

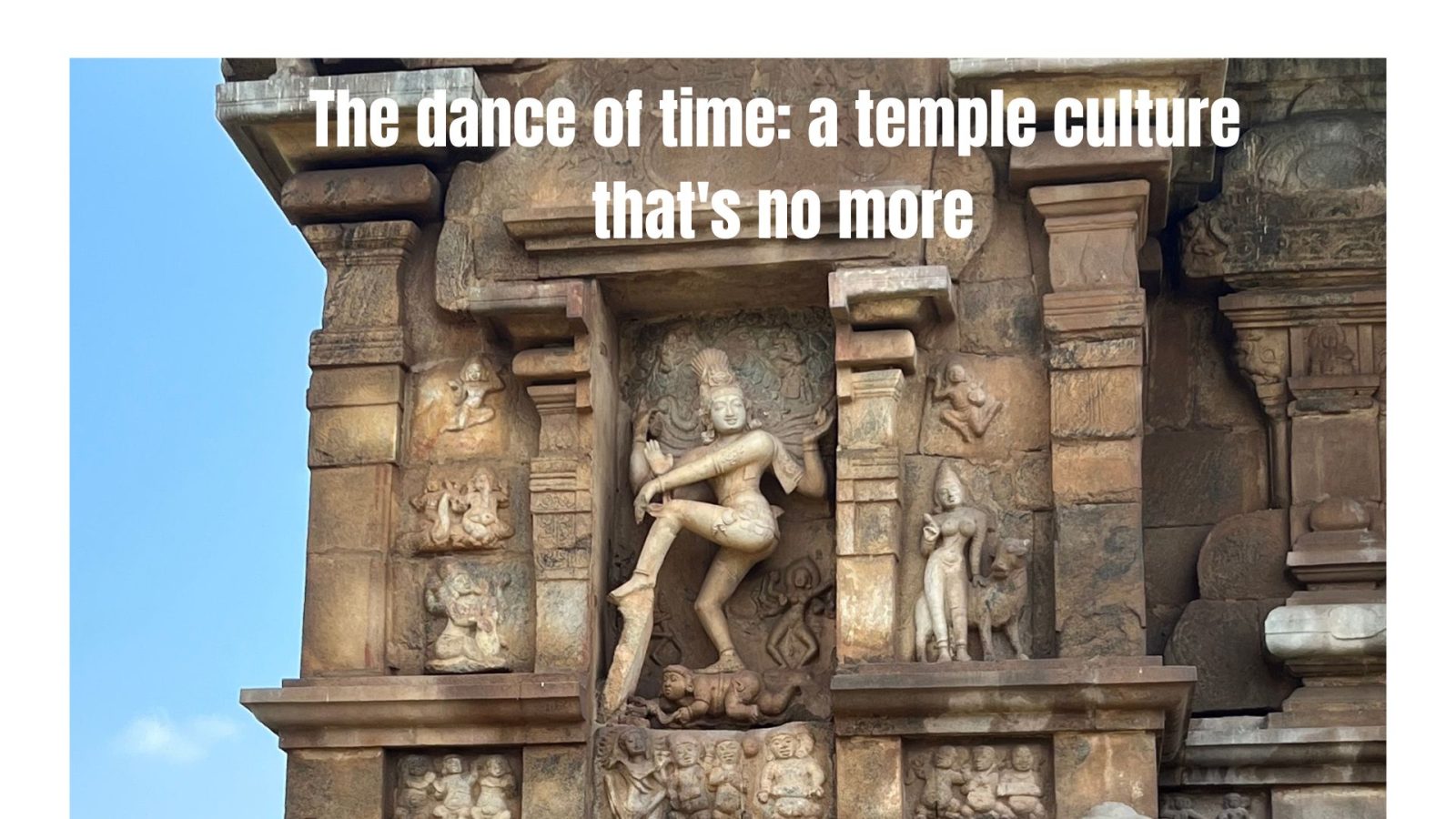

Devadasis were prominently part of temple processions as dancers and singers. Records note that their training in these arts was rigorous and dedicated. With song and dance being such intrinsic function in temple rituals, it is no wonder that temple walls are replete with sculptural depictions of this.

Manickavasagar’s Tiru Porcunnam has one such descript where he describes young, wide-eyed maidens worshipping the Lord with songs, while they adorn him with garlands of flowers, sing songs and light incense and lamps.

One of the most famous dancers of the Chola times was one Anukkiyar Paravai Nankaiyar, a wealthy devadasi. She made many contributions to the Tiruvarur temple, not just in gold, as jewellery or lamps, but also for repairs and for plating of the doors and pillars of the temple.

The Vijayanagara empire too, had a proud tradition of the upkeep and continuation of the temple cultures, where privileges were given to devadasis and their descendants in the ritual practices. We must note here, that one of the greatest rulers of Vijayanagara, Krishnadevaraya, married Chinnadevi, a temple dancer.

Devadasis, one notes, were part of temple rituals from dawn to dusk. They had specific duties as described before, as also being consorts of the Lord, fanning him with the ‘venchamaram’ or the whisk with a handle that we even today see in use during processions of utsava murtis during festival time. Festivals and coronations of kings were not complete without the presence of the devadasi. Children born to devadasis were given rights, especially the girls, who were especially desired, so that they would take forward the family tradition.

What changed? Repeated incursions of Muslim invaders who targeted temples for the hidden wealth they represented, was the first blow. The temple economy hitherto patronised by rajas and other ruling classes, fell into shambles. This resulted in the devadasis losing their sources of income, with the well-defined and codified temple rituals taking a beating.

The coming of the British, and with them, the missionaries, had the devadasis become mere ‘dancing girls’. They came to be referred to as ‘nautch’ girls, and were taken on as performers to the new nobility, the polity that was created by the new western as well as Indian masters. There was social change in the sub-continent, with a redefinition of many of the settled mores. English education played a major role, reinventing the role of many of the social levels, redefining and codifying the caste system into a rigid entity. The sacred link to the temple was broken, and music and dance moved to individual or professional spaces.

Then came the question of morality, and who the devadasi really was. The spirit of the singing and dancing became different; what was once within the confined space of the temple and directed towards a deity as a patron, changed colour. Soon, the ‘nautch’ itself became to be seen as immoral and degraded. The long, historical and cultural connect was broken, and the French Catholic missionary Abbe Dubois equated the devadasi to a prostitute. In a detailed account, he spoke of the devadasis as being “enchanting syrens” being trained to use “allurements and charms” to “accomplish their seductive designs”.

As traditional practices began to crumble, the ‘native’s’ religious practices came into focus. Social reform came into play in a time when most belonging to the devadasi community had lost access to their hereditary status and wealth. Many were penniless, and indeed became the prostitutes they were accused of being. Others took on patrons who were zamindars and dubashes, and who were in seats of power. A once honourable and esteemed community came to be shunned and villainised for affecting ‘public morality’.

With that came the end of the role of the devadasi in temple tradition. And finally, the law came into play, abolishing what had become indeed a derogatory practice.

Today, in every temple, most of the rituals remain in place except for the role of the devadasi. She remains in abstentia, even as her predecessors can be seen dancing on the walls, striking poses that we see on the performing stage even today.

Leave a Reply